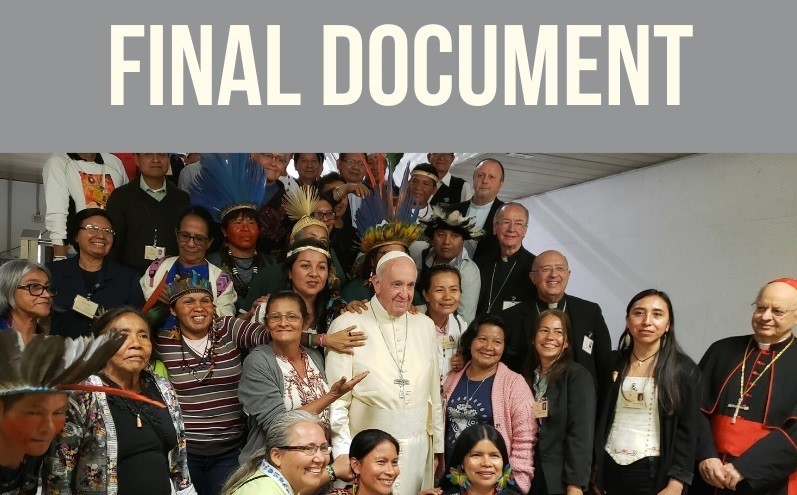

Six weeks have passed since the closing of the Pan-Amazon Synod (Oct. 6-27, 2019), the latest exercise in what Pope Francis has called the “path of synodality which God expects of the Church of the third millennium.” The dust has settled and I have now had a chance to review the Synod’s final document in full, which was originally composed in Spanish and subsequently translated into English by LifeSiteNews in early November due to the absence of an official English text. (Sometime in the past few days, the Vatican finally released an official English translation.)

Another lengthy text (albeit shorter than the Instrumentum Laboris), the Synod’s final document consists of 120 paragraphs divided into five chapters (plus a brief introduction and conclusion) and spans around 25 pages (minus the table of contents and per-paragraph voting record). Verbosity aside, there are several concerning themes in the text – some drearily familiar, others more novel – that warrant a firm critique based on the Church’s perennial Magisterium. Such is the purpose of the present article, which I intend to keep as succinct as possible.

A “New Paradigm” Opposed to Tradition

For starters, as has become the norm with post-conciliar texts, the Amazon Synod’s final document (FD) bears not a single citation to a text issued prior to the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965), thus reinforcing the impression (for the umpteenth time) that many, if not most, of the Church’s current hierarchy considers Vatican II “an end of Tradition, a new start from zero,” to quote the famous lament of Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger (Address to the Bishops of Chile, July 13, 1988). The presence of the phrase “Church of the Second Vatican Council” in the text (n. 87) only confirms this suspicion.

Although FD invokes “Tradition” a few times (e.g., nn. 5, 87, 113), it fails to demonstrate actual continuity with traditional Catholic doctrine (bare assertions do not suffice). Instead, the text is clearly focused on “embracing and practicing” what it calls “the new paradigm of integral ecology, the care of the common home [based on Pope Francis’ eco-encyclical Laudato Si’] and the defense of the Amazon” (FD, n. 4).

Unfortunately, this “new paradigm” is often indistinguishable from naturalistic anthropology (e.g., stressing the need to preserve indigenous beliefs/rituals for their own sake) and United Nations-esque climate change hysteria. It also seems to blur the lines between the proper spheres of Church and State as articulated, for example, by Pope Leo XIII in his 1885 encyclical Immortale Dei:

“The Almighty, therefore, has given the charge of the human race to two powers, the ecclesiastical and the civil, the one being set over divine, and the other over human, things. Each in its kind is supreme, each has fixed limits within which it is contained, limits which are defined by the nature and special object of the province of each, so that there is, we may say, an orbit traced out within which the action of each is brought into play by its own native right. But, inasmuch as each of these two powers has authority over the same subjects, and as it might come to pass that one and the same thing – related differently, but still remaining one and the same thing – might belong to the jurisdiction and determination of both, therefore God, Who foresees all things, and Who is the Author of these two powers, has marked out the course of each in right correlation to the other. …

… There must, accordingly, exist between these two powers a certain orderly connection, which may be compared to the union of the soul and body in man. The nature and scope of that connection can be determined only, as We have laid down, by having regard to the nature of each power, and by taking account of the relative excellence and nobleness of their purpose. One of the two has for its proximate and chief object the well-being of this mortal life; the other, the everlasting joys of heaven. Whatever, therefore, in things human is of a sacred character, whatever belongs either of its own nature or by reason of the end to which it is referred to the salvation of souls, or to the worship of God, is subject to the power and judgment of the Church. Whatever is to be ranged under the civil and political order is rightly subject to the civil authority. Jesus Christ has Himself given command that what is Caesar’s is to be rendered to Caesar, and that what belongs to God is to be rendered to God.” (Immortale Dei, n. 13, 14)

In stark contrast to Leo XIII’s teaching, many of FD’s 120 paragraphs are spent discussing temporal concerns that clearly fall under the State’s jurisdiction, for example: “appropriation and privatization of natural goods, such as water itself; legal logging concessions and illegal logging; predatory hunting and fishing; unsustainable mega-projects (hydroelectric and forest concessions, massive logging, monocultivation, highways, waterways, railways, and mining and oil projects); pollution caused by extractive industries and city garbage dumps; and, above all, climate change” (FD, n. 10).

Now, the Church is certainly not indifferent to the temporal well-being of individuals and societies (she is the most prolific provider of humanitarian services in history!), but as Leo XIII rightly emphasized, it is the State that has “for its proximate and chief object the well-being of this mortal life,” not the Church. The primary way in which the Church contributes to “the prospering of our earthly life” (Immortale Dei, n. 1) is by calling the State to govern “according to the principles of Christian philosophy” (ibid., n. 3) – in other words, by focusing her energy and resources on fulfilling her divine commission to convert “all nations” (Matt. 28:19-20) so that civil authorities, no less than private individuals, profess and protect the one true Faith. When this occurs, as it has in the past, then blessings abound for both Church and State alike.

“Conversion”, Yes, But Not to the Church

Predictably, however, there is very little evidence in FD to suggest even a modest interest in converting non-Catholics, pagan or otherwise, to the Catholic Faith in the Amazon or elsewhere. The word “conversion”, which appears some 32 times, is used almost exclusively in reference to changes in attitude and focus that the Church and her members must supposedly make. Here are a few examples (emphasis added):

- “Listening to the cry of the earth and the cry of the poor and of the peoples of the Amazon with whom we walk, calls us to a true integral conversion, to a simple and modest style of life, all nourished by a mystical spirituality in the style of St Francis of Assisi, a model of integral conversion lived with Christian happiness and joy (cf. LS 12).” (n. 17) (Nowhere in the document is “integral conversion” actually defined, nor is it mentioned that the real St. Francis called people to convert to the Catholic Faith for salvation.)

- “We need to undergo a pastoral conversion in order to be a missionary Church reaching-out.” (n. 20)

- “Our conversion must also be cultural in order to adapt to the other, to learn from the other.” (n. 41)

- “In order to develop the various connections with the whole Amazon and improve its communication, the Church wants to create an All-Amazon Church communication network, to include the various media used by particular churches and other church bodies. Their contribution can resonate with and help in the ecological conversion of the Church and the planet.” (n. 61)

- “For example, recognizing the way in which indigenous peoples relate to and protect their territories is an indispensable measure for our conversion to an integral ecology.” (n. 79) (“Integral ecology” is a novel concept described by Pope Francis in the fourth chapter of Laudato Si’.)

- “To walk together the Church requires a synodal conversion, synodality of the People of God under the guidance of the Spirit in the Amazon.” (n. 86)

As an aside, when newly minted Cardinal Michael Czerny, S.J. was asked to explain “synodality” during the Amazon Synod’s final press conference (Oct. 26), he responded, “I think that the dynamic of the Synod is such that everyone had a sense of what it [synodality] meant because we were doing it. Whether everyone could explain it in words, I’m not so sure, but I’m not sure that that mattered.” In other words, “synodality” (and thus “synodal conversion”) is an empty buzz word.

Regarding “salvation”, the Synod’s final document says that “[e]vangelization in Latin America was a gift of Providence that calls everyone to salvation in Christ” (n. 15), although in the context of recalling past missionary efforts (“was a gift”) and without any mention of the need for faith and Baptism (cf. Mark 16:16). Regarding the here and now, “The Church promotes the integral salvation of the human person, valuing the culture of indigenous peoples, speaking of their vital needs, accompanying movements in their struggles for their rights” (FD, n. 48). It is anyone’s guess as to what “integral salvation” means and whether it is synonymous with the salvation of souls (cf. 1 Pet. 1:9).

How tragic it is that Pope Francis and the Synod Fathers ignored the great missionary encyclicals of the early-to-mid 20th century, including Benedict XV’s Maximum Illud (whose hundredth anniversary was this year), in which the Pontiff who reigned during the First World War took stock of Catholic missionary efforts in his day, stating, “The misfortune of this vast number of souls [i.e., those in need of conversion] is for Us a source of great sorrow. From the days when We first took up the responsibilities of this apostolic office, We have yearned to share with them the divine blessings of the Redemption” (n. 7).[1]

The Spirit (of Dialogue) is Moving

Despite paying lip service to the universal call to salvation in Christ, FD makes it clear that Vatican II’s brand of ecumenism and interreligious dialogue is the real priority. “Ecumenical, inter-religious and inter-cultural dialogue must be taken as indispensable to evangelization in the Amazon (cf. DAp 227),” says FD (n. 24), citing a book-length document published in 2007 following a meeting of Latin American bishops in Aparecida, Brazil – a document which then-Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio was instrumental in producing.

“In the Amazon,” FD continues, “inter-religious dialogue takes place especially with indigenous religions and afro-descendant cults. These traditions deserve to be known, understood in their own expressions and in their relationship with the forest and mother earth. Together with them, Christians, secure in their faith in the Word of God, can enter into dialogue, sharing their lives, their concerns, their struggles, their experiences of God, to deepen each other’s faith and to act together in defense of our common home” (n. 25).

Since when do false religions, which ultimately worship demons (cf. Ps. 95:5; 1 Cor. 10:19-21), and cultural traditions (which, in the Amazon, include infanticide in some cases) “deserve to be known”? From whence did this insistence on dialogue, collaboration, and mutual enrichment come? The answer is simple: the Second Vatican Council. Dr. Romano Amerio (1905-1997), the renowned Swiss-Italian professor of philosophy and consultant to Vatican II’s Central Preparatory Commission, explains in his scholarly tome, Iota Unum (recommended by Bishop Athanasius Schneider in his new book, Christus Vincit, p. 125):

“The word dialogue represents the biggest change in the mentality of the Church after the council, only comparable in its importance with the change wrought be the word liberty in the last [i.e., 19th] century. The word was completely unknown and unused in the Church’s teaching before the council. It does not occur once in any previous council, or in papal encyclicals, or in sermons or in pastoral practice. In the Vatican II documents it occurs 28 times, twelve of them in the decree on ecumenism Unitatis Redintegratio. Nonetheless, through its lightening spread and an enormous broadening in meaning, this word, which is very new in the Catholic Church, became the master-word determining post-conciliar thinking, and a catch-all category in the newfangled mentality.”[2]

One classic use of “dialogue” is found in Nostra Aetate, Vatican II’s Declaration on the Relation of the Church to Non-Christian Religions:

“The Catholic Church rejects nothing that is true and holy in these religions [i.e., Hinduism, Buddhism, various other forms of paganism]. She regards with sincere reverence those ways of conduct and of life, those precepts and teachings which, though differing in many aspects from the ones she holds and sets forth, nonetheless often reflect a ray of that Truth which enlightens all men. …

The Church, therefore, exhorts her sons, that through dialogue and collaboration with the followers of other religions, carried out with prudence and love and in witness to the Christian faith and life, they recognize, preserve and promote the good things, spiritual and moral, as well as the socio-cultural values found among these men.” (Nostra Aetate, n. 2, emphasis added)

This “newfangled mentality” of dialogue permeates the Amazon Synod’s final document, including its recommendations for the proper formation of permanent deacons and priests. In reference to the former, FD asserts, “The program of studies or curriculum for the formation of permanent deacons, in addition to the mandatory subjects, should include topics that foster ecumenical, interreligious, and intercultural dialogue, the history of the Church in the Amazon, affectivity and sexuality, indigenous worldviews, integral ecology, and other cross-cutting themes that are relevant to the diaconal ministry” (n. 106).

Concerning “future priests” (n. 108), which could come from the ranks of married men “who have had a fruitful permanent diaconate” (n. 111), FD states that their formation “should include disciplines such as integral ecology, ecotheology, theology of creation, Indian theologies, ecological spirituality, the history of the Church in the Amazon, Amazonian cultural anthropology, and so on” (n. 108).

There is also a bizarre reference to “youth as a theological topic” (un lugar teológico, “a theological place”, in the original Spanish) who are “committed to dialogue, ecologically sensitive and attentive to our common home” (n. 33).

“Seeds of the Word”

The key to understanding the post-conciliar obsession with dialogue is the phrase “seeds of the Word”, which appears in FD four times (nn. 14, 43, 54, 55) but which previously appeared in Vatican II’s Decree on the Mission Activity of the Church, Ad Gentes:

“In order that they may be able to bear more fruitful witness to Christ, let them [Catholics] be joined to those men [non-Catholics] by esteem and love; let them acknowledge themselves to be members of the group of men among whom they live; let them share in cultural and social life by the various undertakings and enterprises of human living; let them be familiar with their national and religious traditions; let them [Catholics] gladly and reverently lay bare the seeds of the Word which lie hidden among their fellows.” (Ad Gentes, n. 11, emphasis added)

Concerning this phrase, Professor Amerio explains, “It is true that the Fathers of the early centuries, such as Justin Martyr and the Alexandrian writers, taught that the seed of the Word [i.e., Christ Himself; cf. John 1] had been scattered abroad among the human race; but they also taught that man’s religious insights had been darkened by the effects of original sin, and even by evil spirits [i.e., demons] who, as St. Augustine says, tempted man to adore them or to adore other mere mortals.”[3]

As Professor Amerio notes, the early Church Fathers who employed the concept of “seeds of the Word” did not do so in order to affirm paganism as intrinsically good. St. Justin Martyr (d. ca. A.D. 165), for example, used the phrase “seeds of truth” in his First Apology, but in the context of arguing that all men are ultimately dependent upon Divine Revelation:

“For Moses is more ancient than all the Greek writers. And whatever both philosophers and poets have said concerning the immortality of the soul, or punishments after death, or contemplation of things heavenly, or doctrines of the like kind, they have received such suggestions from the prophets as have enabled them to understand and interpret these things. And hence there seem to be seeds of truth among all men; but they are charged with not accurately understanding [the truth] when they assert contradictories.” (First Apology, 44, emphasis added)

Much closer to our own times, Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre (1905-1991) – the Apostolic Delegate to French-speaking Africa (1948-1962), first Archbishop of Dakar (Senegal), Superior General of the Holy Ghost Fathers (1962-1968), and one of the greatest Catholic missionaries of the 20th century – wrote the following in reference to Nostra Aetate (quoted above) and the Council’s novel concept of “dialogue” in his classic work, They Have Uncrowned Him:

“What? I should respect the polygamy and the immorality of Islam? Or the idolatry of Hinduism? To be sure, these religions can keep some sound elements, signs of natural religion, natural occasions for salvation; even preserve some remainders of the primitive revelation (God, the fall, a salvation), hidden supernatural values which the grace of God could use in order to kindle in some people the flame of a dawning faith. But none of these values belongs in its own right to these false religions. … The wholesome elements that can subsist still belong by right to the sole true religion, that of the Catholic Church; and it is this one alone that can act through them.”[4]

Regarding the effects of “dialogue” on the Church’s missionary mandate, Archbishop Lefebvre offers a sobering assessment:

“To stand before non-Christians, without telling them that they need the Christian religion, that they cannot be saved except through Our Lord Jesus Christ, is an inhuman cruelty. … This ‘dialogue’ is anti-missionary to the highest degree! Our Lord sent His Apostles not to dialogue, but to preach! Now, as it is this spirit of liberal dialogue that has been inculcated since the Council in the priests and the missionaries, we can understand why the conciliar Church has completely lost the missionary zeal, the very spirit of the Church!”[5]

Thus, here we are with the Amazon Synod, whose final document claims that the Church is the one in need of conversion, not the Amazonian peoples.

Women’s “Ministries”

Before we conclude this survey, there are a couple more controversial topics found in FD that must be addressed.

First, in a sub-section entitled, “The time for women’s presence”, we find five paragraphs devoted to the subject of female involvement in the Church (nn. 99-103), something which FD emphasizes “[t]he Magisterium of the Church since the Second Vatican Council has highlighted” (n. 99, emphasis added). After rightly commending the role that women play in transmitting the Faith (first and foremost, to their own children), FD makes a quantum leap of shocking proportions:

“We assure women’s place in leadership and formation. We ask that the Motu Propio of St. Paul VI, Ministeria quaedam (1972) be revised, so that women who have been properly trained and prepared can receive the ministries of Lector and Acolyte, among others to be developed.” (n. 102, emphasis added)

For those not familiar with Ministeria Quaedam, it was an Apostolic Letter of Pope Paul VI concerning the Church’s minor orders (porter, lector, exorcist, and acolyte) – primarily liturgical roles that have existed since ancient times and “by which, as by various steps, one advances towards the priesthood” (Council of Trent, Can. 2 on the Sacrament of Orders; D.H. 1772). In the name of Vatican II, Paul VI chose to suppress two of the four minor orders (porter and exorcist), as well as one of the traditional major orders (subdeacon), and decreed that the remaining “orders” of lector and acolyte would henceforth be called “ministries”, with acolytes absorbing “the functions of the subdiaconate.”[6]

The notion that women could validly “receive the ministries of Lector and Acolyte” – roles which have always been reserved to men – is absolutely opposed to Sacred Tradition and canon law. Aside from St. Paul’s clear teaching, “Let women keep silence in the churches” (1 Cor. 14:34), it has always been forbidden for women to serve near the altar, which is precisely the acolyte’s role. Pope Benedict XIV (r. 1740-1758), for example, testified in his encyclical Allatae Sunt (On the Observance of Oriental Rites):

“Pope Gelasius [r. 492-496] in his ninth letter (chap. 26) to the bishops of Lucania condemned the evil practice which had been introduced of women serving the priest at the celebration of Mass. Since this abuse had spread to the Greeks, Innocent IV [r. 1243-1254] strictly forbade it in his letter to the bishop of Tusculum: ‘Women should not dare to serve at the altar; they should be altogether refused this ministry.’ We too have forbidden this practice in the same words in Our oft-repeated constitution Etsi Pastoralis, sect. 6, no. 21.” (Allatae Sunt, n. 29)

Even the post-conciliar Code of Canon Law (promulgated in 1983) specifically restricts “the ministries of lector and acolyte” to “[l]ay men” (can. 230 §1).

The request for official ministerial status for women is closely tied to the Modernist call for female deacons, mentioned in FD as follows:

“In the many consultations carried out in the Amazon, the fundamental role of religious and lay women in the Church of the Amazon and its communities was recognized and emphasized, given the wealth of services they provide. In a large number of these consultations, the permanent diaconate for women was requested. This made it an important theme during the Synod. The Study Commission on the Diaconate of Women which Pope Francis created in 2016 has already arrived as a Commission at partial findings regarding the reality of the diaconate of women in the early centuries of the Church and its implications for today [see here a report on those ‘findings’]. We would therefore like to share our experiences and reflections with the Commission and we await its results.” (n. 103)

The First Council of Nicaea (A.D. 325) addressed this issue long ago with great clarity: “We have made mention of the deaconesses, who have been enrolled in this position, although, not having been in any way ordained, they are certainly to be numbered among the laity” (Can. 19, emphasis added).[7] Furthermore, the International Theological Commission published a lengthy study on the subject in 2002 which concludes by observing, “The deaconesses mentioned in the tradition of the ancient Church – as evidenced by the rite of institution and the functions they exercised – were not purely and simply equivalent to the deacons….” (For a fuller treatment of this subject, see John Vennari’s 2016 article, “Deaconesses,” Strictly Speaking, Never Existed.)

Inculturated Liturgy

Lastly, the Amazon Synod’s final document concludes with a call for “the elaboration of an Amazonian rite that expresses the liturgical, theological, disciplinary and spiritual patrimony of the Amazon” (n. 119), a topic broached during the first working session of the Synod. Not surprisingly, Vatican II is invoked as the source which “created possibilities for liturgical pluralism” (n. 116). It seems that the vast majority of Synod Fathers are not satisfied with the pluralism already offered vis-à-vis the Novus Ordo Missae and want to impose further liturgical novelties (only 29 of them voted against paragraph 119 of FD). It is reasonable to suspect that such novelties will include the same sort of syncretism and idolatry we saw on display during the Synod itself.

Sadly, this is the logical end of Vatican II’s Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy, Sacrosanctum Concilium, which states: “Provisions shall also be made, when revising the liturgical books, for legitimate variations and adaptations to different groups, regions, and peoples, especially in mission lands, provided that the substantial unity of the Roman rite is preserved; and this should be borne in mind when drawing up the rites and devising rubrics. … In some places and circumstances, however, an even more radical adaptation of the liturgy is needed, and this entails greater difficulties” (nn. 38, 40).

One wonders how “the substantial unity of the Roman rite” can possibly be “preserved” when “radical adaptation of the liturgy” is something presented as legitimate and necessary. The Novus Ordo itself has already decimated the liturgical unity that existed for centuries in the Roman Church; the introduction of national or region-specific rites, such as the Zairian rite – which Pope Francis recently offered in St. Peter’s Basilica – will only further the fragmentation. (See our 2019 CFN Conference page for more resources on “The New Mass: Fifty Years of Problems”.)

Conclusion: Vatican II with an Amazonian Face

After following the Synod as it unfolded, and now having surveyed its final document, there is only one phrase that comes to mind which adequately describes the event: it was, and is, Vatican II with an Amazonian face. And the Amazonian face, so it seems, is merely an indigenous costume for ongoing Modernist revolution.

In response to this revolution, may the movement for Traditional Catholic Restoration continue to grow throughout the coming new year. Our Lady of Fatima, pray for us!

UPDATED (12/9/2019): After posting this article, I recalled a rather humorous parody video (an edited version of a promo video released by Vatican News) that someone posted in reply to me on Twitter. It really captures the essence of the Synod being an indigenous costume for ongoing Modernist revolution:

[1] See also Pius XI’s Rerum Ecclesiae (Feb. 28, 1926) and Pius XII’s Evangelii Praecones (June 2, 1951) for further reading.

[2] Romano Amerio (trans. Rev. Fr. John P. Parsons), Iota Unum: A Study of the Changes in the Catholic Church in the XXth Century (Kansas City: Sarto House, 1996), p. 347.

[3] Ibid., pp. 572-573.

[4] Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre, They Have Uncrowned Him: From Liberalism to Apostasy, The Conciliar Tragedy (Kansas City: Angelus Press, 1988), p. 177.

[5] Ibid., p. 181.

[6] The minor orders and subdiaconate have, of course, been retained by traditional societies of priests and religious orders, beginning with the Society of St. Pius X (SSPX).

[7] Fr. William A. Jurgens, The Father of the Early Fathers Volume I (Collegeville: The Liturgical Press, 1970), p. 286 (n. 651y).